Nabil DEEB

Arzt – Physician – Doctor

PMI-Ärzteverein e.V.

Palästinamedico International Ärzteverein – ( P M I ) e.V.

Palestine Medico International Doctors Association ( P.M.I.) registered association

Department of Medical Research

Département de la recherche médicale

P.O. Box 20 10 53

53140 Bonn – Bad Godesberg / GERMANY

e.mail: [email protected]

Dr. Nabil Abdul Kadir DEEB

GERMANY 53137 Bonn

e.mail: [email protected]

anorectal malformations associated with urologic and neurologic malformations caused by the effects of depleted uranium ( = DU ) on the stateless Palestinian refugee child Zina .

nabildeeb-syndrome

Abstract :-

The 3 years-old stateless Palestinian child Zina has since her birth a deformity of the colon, a major malformation of the anus and a fistula of the common pathology of the bladder and colon with an atrophy of the colon desendens.

The little girl Zina was operated on emergency and Colostomy (naturalis) Colostomy in the abdominal wall for defecation (in a collection bag) on the right colon asendens as a substitute for the anus, so can the little girl stay alive and for later the ascending colon , colon asendens`, to strengthen and further more for specific diagnoses and special operations. The little girl Zina must be re-operated on several occasions in a special pediatric surgery clinic specializing in pediatric surgery for rectal malformations and complications in the U.S., Canada or Europe. These diseases , anorectal malformations associated with urologic and neurologic malformations , of the child Zina are caused by the effects of depleted uranium ( = DU ) on the child Zina and on her mother during the early pregnancy of her mother in the IRAQ - BAGHDAD, because they lived in Baghdad in areas, where contamination depleted uranium ( = DU ) was and is high .

The little girl, Zina Mohammed Hussein Al - Gazar

the effects of depleted uranium ( = DU) on the child Zinaanorectal malformations associated with urologic and :

neurologic malformations Colostomy (naturalis) Colostomy in the abdominal wall for defecation (in a collection bag) on the right colon asendens .

the stateless Palestinian refugee child Zina

Infection

Colostomy (naturalis) Colostomy in the abdominal wall for defecation (in a collection bag) on the right colon asendens as a substitute for the anus, so can the little girl stay alive the stateless Palestinian refugee child Zina .

The little girl, Zina Mohammed Hussein Al - Gazar

the effects of depleted uranium ( = DU) on the child Zinaanorectal malformations associated with urologic and :

neurologic malformations Colostomy (naturalis) Colostomy in the abdominal wall for defecation (in a collection bag) on the right colon asendens

The little girl, Zina Mohammed Hussein Al - Gazar was born at 02. November 2009 in Baghdad - Iraq. She is a child stateless Palestinian refugee, and living at the time of political unrest and expelled from Iraq in the UNHCR - the refugee camp in the desert between Iraq and Syria on Syrian territory under temporary in care and contactor of the UNHCR and waits with her parents and two healthy sisters to live in a country anywhere in the world through the agency, UNHCR – Geneva .

When the intake of these above mentioned refugees is uncertain and often lasts two to five years waiting in UNHCR - refugee camp in the desert near the Iraqi-Syrian border .

The 3-years-old girl suffering from birth under

"" Anorectal malformation ""

(= congenital malformations of the rectum and the anus) as a result of the

developmental disorder of embryo in the early stages of pregnancy of her mother

because of the radiation depleting effect of the environment in the home of

their mother in Baghdad .

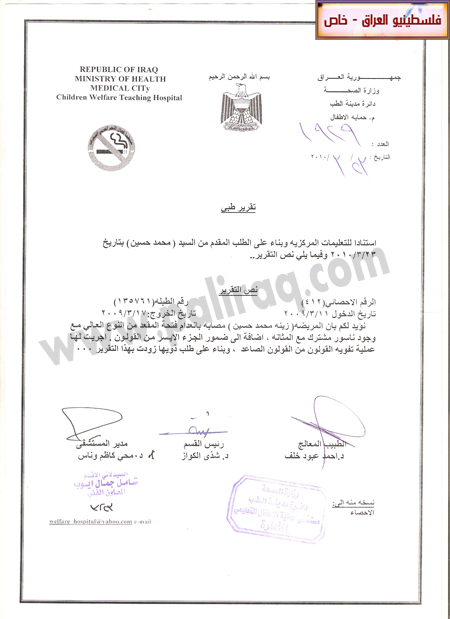

It was a temporary colostomy (colostomy =) at the university hospitals - Baghdad in March 2010 created the child, give the child a temporary chair to give way, which is for her vital moment .

Another treatment for the child in the Palestinian desert in a refugees camp was and still is not possible for many reasons .

The child needs urgent and more vital operational treatment as a pulling operation (posterior sagittal anorectal PSARP = plastic) with a minimally invasive surgery is used .

Such further treatment in a special children's surgery – clinic for example in U.S.A , Canada , in Europe, for example in ,Finland, Norway, Sweden, France or in the Federal Republic of Germany in a department of pediatric surgery .

The three-years-old girl Zina is waiting since her birth to 02 November 2009 with her two little healthy sisters and her parents in the desert between the Iraqi and Syrian deserts in - the refugees UNHCR camp to a reasonable medical surgical treatment in a country .

Without appropriate treatment for the child's life little girl Zina would be destroyed forever because permanent serious infections and cancer degeneration .

In this context, I refer-so called International Humanitarian Law .

In comparison to the treatment of children in the rest of the world as in Europe , Canada or the U. S. A .

These diseases , anorectal malformations associated with urologic and neurologic malformations , of the child Zina are caused by the effects of depleted uranium (DU DU) on the child Zina and on her mother during the early pregnancy of her mother in the IRAQ - BAGHDAD, because they lived in Baghdad in areas where the contamination depleted uranium ( = DU ) was and is high.

Ref. See nabildeeb:-

http://www.springermedizin.at/artikel/18287-neue-therapie-bei-blutkrebs-in-aussicht

I.:-

I refer to the latest published medical contribution of colleagues W. J. H. Goossens,1 I. de Blaauw,2,3 M. H. Wijnen,2 R. P. E. de Gier,1 B. Kortmann,1 and W. F. J. Feitz1 ,Department of Urology, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands 2Department of Surgery/Pediatric Surgery, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands 3Department of Pediatric Surgery, Erasmus MC, Sophia Children’s Hospital, Rotterdam, The Netherlands W. F. J. Feitz

Pediatric Surgery InternationalPediatr Surg Int. 2011 October; 27(10): 1091–1097.

Published online 2011 July 30. doi: 10.1007/s00383-011-2959-4PMCID: PMC3175030Urological anomalies in anorectal malformations in The Netherlands: effects of screening all patients on long-term outcome

W. J. H. Goossens,1 I. de Blaauw,2,3 M. H. Wijnen,2 R. P. E. de Gier,1 B. Kortmann,1 and W. F. J. Feitz1

1Department of Urology, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands 2Department of Surgery/Pediatric Surgery, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands 3Department of Pediatric Surgery, Erasmus MC, Sophia Children’s Hospital, Rotterdam, The Netherlands W. F. J. Feitz, Phone: +31-24-3613735, Fax: +31-24-3541031, Email: [email protected] author.

Author information ► Copyright and License information ►

Copyright © The Author(s) 2011

Go to:Abstract.Introduction

Urological anomalies are frequently seen in patients with anorectal malformations (ARM) and can result in upper urinary tract deterioration. Whether the current method of screening is valid, adequate and needed for all patients is not clear. We, therefore, evaluated the urological screening methods in our ARM patients for changes in urological treatment, outcome and follow-up.

Methods

The medical records of 331 children born with an ARM in the period 1983–2003 were retrospectively studied. Documentation of diagnosis, screening method, urological anomalies, treatment, complications, follow-up and outcome were measured.

Results

The overall incidence of urological anomalies was 52%. The incidence of urological anomalies and urological follow-up time decreased with diminishing complexity of the ARM. Hydronephrosis, vesico-urethral reflux, lower urinary tract dysfunction and urinary incontinence were encountered most. Treatment invasiveness increased with the increase of complexity of an ARM. Lower urinary tract dysfunction needing urological care occurred in 43% in combination with lumbosacral or spinal cord anomalies and in 8% with no abnormalities in the lumbosacral-/spinal region.

Conclusions

Urological anomalies in patients with complex ARM are more severe than in patients with less complex ARM. Ultrasonography of the urinary tract should be performed in all patients. Voiding cysto-urethrography can be reserved for patients with dilated upper urinary tracts, urinary tract infections or lumbosacral and spinal abnormalities. All patients with complex ARM need urodynamic investigations. When using these indications, the screening for urological anomalies in ARM patients can be optimized with long-term follow-up in selected patients.

Keywords: Anorectal malformation, Urological anomaly, VACTERL, Ultrasonography, Voiding cysto-urethrography, Urodynamic investigation

Go to:Introduction.Anorectal malformations (ARM) are congenital anomalies of the anorectum which cover a wide spectrum of anatomical anomalies, characterized by an absence of a normally formed anus at its normal position within the perineum [1, 2]. ARM range from complex anomalies of the hindgut and urogenital organs, such as a cloaca, to less complex perineal fistulas or vestibular fistulas [1]. It is well known that children with ARM show a high incidence of associated anomalies in other organ systems, which often have a high morbidity and mortality by themselves [3–6]. The overall incidence of these associated anomalies is more than 60% [7]. Urological anomalies are frequently seen in patients with ARM and can result in severe deterioration of the upper urinary tract when treated inadequately [1, 8–11]. An attempt to detect urological anomalies is necessary, as a lack of early measurements can lead to significant damage to the upper urinary tract [12–14]. Previous studies recommended that all children with ARM should undergo an ultrasonography of the urinary tract in the neonatal period [8, 12]. To detect vesico-ureteral reflux, all patients with a dilatation of the upper urinary tract should undergo a voiding cysto-urethrography [8, 12]. Furthermore, sacral X-ray and an ultrasonography of the spinal cord should be made to detect lumbosacral anomalies or defects of the spinal cord [13, 15]. Patients with ARM and a coexisting anomaly of the lumbosacral spinal column or spinal cord are more likely to have lower urinary tract dysfunction. However, whether screening for urological anomalies in all patients with ARM improves urological treatment and outcome has not been investigated. The necessity of screening the whole spectrum and whole population of ARM patients is unclear. The urological anomalies found with the current screening methods may not have influenced treatment and outcome in the less complex cases. This study aimed to study the incidence of urologic anomalies associated with ARM and the relationship between the severity of the ARM and the incidence of these urological defects with a long-term outcome evaluation. Urologic follow-up, treatment and outcome are studied to test whether there is a difference in treatment regime between the various groups of ARM patients. Based on these data, recommendations are formulated regarding the screening for urological anomalies in patients with ARM.

Go to:Materials and methods.Patients

A retrospective evaluation of the medical records was performed for all children with ARM, referred to the department of pediatric surgery of the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center from 1983 to 2003. Within this period 351 patients were seen with this diagnosis, of which 20 were excluded due to insufficient or incomplete data, resulting in a cohort of 331 patients. In the medical records, patients were mostly classified according to the Wingspread classification. However, recently the Krickenbeck classification is accepted and most used to describe and classify ARM. For the present study the Krickenbeck classification was used and our patients were re-classified accordingly. We further divided our patients in complex malformations and less complex malformations. We defined the ARM as complex malformations when the medical record mentioned cloacal malformations, bladder fistulas, urethral fistulas (prostatic and bulbar), vaginal fistulas or no fistula. We considered them less complex malformations when there was mentioning of perineal fistulas or anterior displaced anus, vestibular fistulas or anal stenosis. Rectal atresias were also considered as less complex ARM as these malformations have similar good outcomes as perineal- or vestibular fistulas. The urological records of the patients who were also seen by a pediatric urologist were reviewed as well. These files included screening results of clinical examination and additional investigations to trace urologic anomalies, including treatment and follow-up time. Different treatment options were taken together and grouped into modalities of increasing invasiveness (expectative, conservative measurements, medication and surgery).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS 16.0. The incidence and treatment of the different urological anomalies were analyzed using the Chi-Square Test and Fisher’s Exact Test. The statistical calculations of the follow-up time were done with the One-way ANOVA Test. A p value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Go to:Results.Three hundred thirty-one patients with ARM were evaluated of which 48% were female and 52% were male. The patients had a variety in the severity of ARM (Table 1). In one female and one male patient the type of ARM was unclassified. These patients were not taken into evaluation during the rest of the study. Forty-six percent of male patients and 17% of female patients had a complex ARM. Urological anomalies were found in 172 cases (52%). The incidence of urological anomalies decreased with decreasing complexity of the ARM (Table 1). Remarkably, rectal atresias, which are considered less complex malformations with good prognosis had a high incidence of urological anomalies. Urological follow-up time ranged from 48 months for the youngest, to 300 months for the oldest patients. Mean follow-up time in the entire group was 40 months and decreased with decreasing severity of ARM (Table 1). The four most seen urological anomalies in patients with ARM were hydronephrosis, vesico-ureteral reflux, lower urinary tract dysfunction and urinary incontinence with a total incidence of 24, 18, 14 and 12%, respectively. In all four anomalies, the incidence of the urological anomalies diminished with decreasing complexity of ARM (Tables 2, ,33).

Table 1

Cohort characteristicsTable 2

Incidence of most common urological anomalies in complex ARMTable 3

Incidence of most common urological anomalies in less complex ARMTreatment of urological anomalies in ARM

Treatment of hydronephrosis is similar in patients with complex and less complex ARM (Table 4). Antibiotic prophylaxis was given in 53% of the patients with hydronephrosis in the complex ARM group, compared to 36% in the less complex group. The number of patients receiving surgical treatment was practically equal. Reimplantations of ureters were performed in three patients with complex ARMs and two patients with less complex ARMs. A pyeloplasty was done in one patient in both groups. A nephrectomy was performed in two patients with a complex ARM. Vesicostomy or uretero-cutaneostomy was performed in two patients with a complex ARM and three patients in the less complex ARM group. Treatment of vesico-ureteral reflux also was comparable in both groups (Table 5). The two patients with less complex ARM and reflux underwent a reimplantation of the ureter. In the complex ARM group, reimplantation of the ureter was performed in six cases, two patients required a nephro-ureterectomy, and one patient got a vesicostomy.

Table 4

Treatment of hydronephrosis in ARMTable 5

Treatment of vesico-ureteral reflux in ARMIn patients with lower urinary tract dysfunction, surgery was exclusively performed in patients with complex ARM (Table 6). Of these 11 patients, 3 underwent an augmentation of the bladder, 5 needed a vesicostomy and 3 received a Bricker urinary deviation. The amount of patients needing clean intermittent catheterization was the same in the complex and less complex group. Anticholinergic medication was prescribed in 50% of the patients with less complex ARMs, compared to 32% in the complex ARM group. In the complex ARM group 35% of the patients needed surgical intervention to treat urinary incontinence compared to 6% of the patients with less complex ARM (Table 7). One patient in the less complex ARM group was treated by a reconstruction of the bladder neck. Of the patients receiving surgery in the complex ARM group, four patients received a Bricker urinary deviation, three patients received a vesicostomy, and in one patient a reconstruction of the bladder neck was performed.

Table 6

Treatment of lower urinary tract dysfunctionTable 7

Treatment of urinary incontinence in ARMLumbosacral-/spinal cord anomalies and lower urinary tract dysfunction in ARM

The incidence of anomalies of the lumbosacral spine and spinal cord defects are shown in Table 8. Of the patients with a complex ARM 39% also had a lumbosacral or spinal cord anomaly compared to 8% of the patients with a less complex ARM. Subsequently, 43% of the patients with a lumbosacral-/spinal cord anomaly associated with their ARM suffer from lower urinary tract dysfunction (Table 9). However, 8% of the children without any anomaly of the lumbosacral spine or spinal cord also had lower urinary tract dysfunction.

Table 8

Incidence of lumbosacral-/spinal cord anomalies in ARMTable 9

Lumbosacral-/spinal cord anomalies and lower urinary tract dysfunction in ARM (p < 0.001)Go to:Discussion.Urological anomalies are frequently seen in patients with ARM. This study aimed to evaluate the need of screening for urological anomalies in patients with ARM. We aimed to classify all ARMs according to fistula level (Krickenbeck International classification) [16]. However, as the Wingspread classification [17] was mostly used in the time period our patients were operated to determine the operative approach, data to classify the ARM according to fistula level were not always available. Due to insufficient data, it was impossible in urethral fistulas to distinguish between a prostatic fistula, a complex condition that is frequently accompanied by urological pathology, and bulbar fistula, a relatively less severe malformation with less urological problems [18]. We also know that a true vaginal fistula is a rare and previously overestimated malformation [19]. Thus, some of the vaginal fistulas in our series are also likely to have been vestibular fistulas, a less complex condition. For analytical purposes of our study, we grouped our patients into two categories: complex and less complex ARM. Because of the enormous variety in treatment options for the urological anomalies as well, different treatment options were grouped into modalities of increasing invasiveness (expectative, conservative measurements, medication and surgery).

More than 50% of the patients with an ARM within our cohort suffered from one or more associated urological anomalies. Most series show a similar incidence of 25–50% [1, 4–6, 8–10, 14, 15, 20, 21]. The differences in these studies are mostly due to the fact that in some of these studies (as in our study) all urological anomalies were evaluated, whereas in other series not all anomalies are taken into the evaluation (e.g., cryptorchism). Furthermore, urological anomalies occur more frequently in complex forms of ARM. As our hospital is a referral centre for complex pediatric surgery, it might be that more complex cases are presented than in other patient cohorts (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Incidence of urological anomalies in ARM. Asterisk urethral fistula: prostatic- and bulbar fistulas, double asterisk perineal fistula: including anterior displaced anusIn general, patients with complex ARM more often suffer from severe urological anomalies than patients with less complex ARM. This is seen in the amount of invasive treatments these patients require. Hydronephrosis was encountered most (24%). This corresponds well with data retrieved from other series [4–6, 10, 20]. The main difference in treatment of hydronephrosis in patients with complex and less complex ARM was found in the amount of patients receiving antibiotic prophylaxis. As patients with a complex ARM often have fistula between terminal rectum and urinary tract, hydronephrosis is mostly treated with antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent upper urinary tract infections. In less complex ARM, however, more often an expectative approach is chosen. This may be due to the fact that the risk of infection is considered to be lower because there is no fistula to the urinary tract but to the vestibulum or the perineum. The finding of hydronephrosis in patients with less complex ARM did not have many consequences for treatment. One could debate the need to screen every patient with ultrasonography of the urinary tract. However, hydronephrosis is an anomaly that can result from other additional uropathology (e.g., vesico-ureteral reflux) needing therapy. Furthermore, ultrasonography is non-invasive and it is a relatively easy way to detect other anomalies of the urinary tract. Therefore, we acknowledge the importance of ultrasonography of the urinary tract and recommend carrying it out it in all patients with ARM.

Vesico-ureteral reflux was seen in 18% of the patients, and a decreasing incidence was seen with decreasing severity of the ARM. Previous studies showed an incidence ranging from 14 to 27% [9, 10, 15, 22]. In our population, vesico-ureteral reflux was mostly encountered performing a voiding cysto-urethrography (VCUG). Because not all infants in the early part of this series received a VCUG, the true incidence may be underestimated. Most cases of vesico-ureteral reflux in our population were treated with a conservative approach using antibiotic prophylaxis. Only a small group of patients needed surgical intervention to prevent damage to the upper urinary tract. Patients with a complex ARM were more likely to have severe vesico-ureteral reflux that qualifies for a surgical correction than children with less complex ARM. Nevertheless, this does not mean that patients with less complex ARM never had severe reflux. As severe vesico-ureteral reflux often goes hand in hand with dilatation of the upper urinary tract, we advise VCUG-evaluation in all patients with ARM who show a dilatation of the upper urinary tract on ultrasonography. Also, patients who have had a urinary tract infection should undergo VCUG-screening. This corresponds with recommendations made by others [4, 6, 8–10, 12].

Many patients with ARM have lower urinary tract dysfunction that causes clinically important urological problems such as incontinence and upper urinary tract deterioration [1, 12, 13, 15]. Lower urinary tract dysfunction is defined as any functional anomaly of the bladder and/or urethra that has negative influence on voiding function. In patients with ARM, voiding dysfunction usually is neuropathic in origin and is commonly caused by associated defects of the lumbosacral spinal column (e.g., sacral agenesis) or abnormalities in the spinal cord (e.g., tethered spinal cord) [13, 15, 23]. Less commonly, iatrogenic pelvic nerve damage acquired during reconstruction of the ARM causes voiding dysfunction [2, 15, 24, 25].

Patients with complex ARM suffered significantly more often from lumbosacral-/spinal cord anomalies than patients with a less complex ARM. Moreover, patients with ARM and lumbosacral or spinal cord anomaly more often had lower urinary tract dysfunction, with voiding problems as a consequence. The designated diagnostic method to encounter lower urinary tract dysfunction is an urodynamic investigation. In the present study, urodynamic assessment was only performed in selected cases. Other groups have recommended urodynamic investigation in all patients with ARM that have sacral agenesis or a defect of the spinal cord [12, 15]. According to their data only 2% of the children without lumbosacral-/spinal cord anomalies who have lower urinary tract dysfunction will be missed. However, according to our study, retrieved from a much larger population of patients with ARM, 8% of the patients without lumbosacral or spinal cord anomalies will have lower urinary tract dysfunction and will be missed following that recommendation. Lower urinary tract dysfunction has its highest incidence in complex ARM, has a tendency to be more severe in patients with complex ARM and it more frequently requires invasive treatment. We, therefore, recommend urodynamic screening of all patients with complex ARM. However, as patients with less complex ARM are not free of risk to develop lower urinary tract dysfunction, clinical follow-up of the miction pattern has to be done as soon as the patient reaches an age where full voiding control may be expected to encounter subclinical voiding problems.

In conclusion, urological anomalies in patients with complex ARM are more severe than in patients with less complex ARM. Ultrasonography of the urinary tract should be performed in all patients. Voiding cysto-urethrography can be reserved for patients with dilated upper urinary tracts, lumbosacral and spinal abnormalities, or in case of additional urinary tract infections. All patients with complex ARM need urodynamic investigations. When using these indications, the screening for urological anomalies in ARM patients can be optimized with long-term follow-up in selected patients.

Go to:Open Access.This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Go to:References.1. Levitt MA, Pena A. Anorectal malformations. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;26(2):33. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

2. Pena A. Anorectal malformations. Semin Pediatr Surg. 1995;4(1):35–47. [PubMed]

3. Hassink EA, Rieu PN, Hamel BC, Severijnen RS, vd Staak FH, Festen C. Additional congenital defects in anorectal malformations. Eur J Pediatr. 1996;155(6):477–482. doi: 10.1007/BF01955185. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

4. Mittal A, Airon RK, Magu S, Rattan KN, Ratan SK. Associated anomalies with anorectal malformation (ARM) Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71(6):509–514. doi: 10.1007/BF02724292. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

5. Ratan SK, Rattan KN, Pandey RM, Mittal A, Magu S, Sodhi PK. Associated congenital anomalies in patients with anorectal malformations—a need for developing a uniform practical approach. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39(11):1706–1711. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.07.019. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

6. Stoll C, Alembik Y, Dott B, Roth MP. Associated malformations in patients with anorectal anomalies. Eur J Med Genet. 2007;50(4):281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2007.04.002. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

7. Rintala RJ. Congenital anorectal malformations: anything new? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48(Suppl 2):S79–S82. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181a15b5e. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

8. Boemers TM, Jong TP, Gool JD, Bax KM. Urologic problems in anorectal malformations. Part 2: functional urologic sequelae. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31(5):634–637. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(96)90663-6. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

9. McLorie GA, Sheldon CA, Fleisher M, Churchill BM. The genitourinary system in patients with imperforate anus. J Pediatr Surg. 1987;22(12):1100–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(87)80717-0. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

10. Rich MA, Brock WA, Pena A. Spectrum of genitourinary malformations in patients with imperforate anus. Pediatr Surg Int. 1988;2–3:110–113.

11. Wiener ES, Kiesewetter WB. Urologic abnormalities associated with imperforate anus. J Pediatr Surg. 1973;8(2):151–157. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(73)80078-8. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

12. Boemers TM, Beek FJ, Bax NM. Review. Guidelines for the urological screening and initial management of lower urinary tract dysfunction in children with anorectal malformations—the ARGUS protocol. BJU Int. 1999;83(6):662–671. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00965.x. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

13. Jindal B, Grover VP, Bhatnagar V. The assessment of lower urinary tract function in children with anorectal malformations before and after PSARP. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2009;19(1):34–37. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1039027. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

14. Parrott TS. Urologic implications of imperforate anus. Urology. 1977;10(5):407–413. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(77)90122-4. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

15. Boemers TM, Beek FJ, Gool JD, Jong TP, Bax KM. Urologic problems in anorectal malformations. Part 1: Urodynamic findings and significance of sacral anomalies. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31(3):407–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(96)90748-4. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

16. Holschneider A, Hutson J, Pena A, Beket E, Chatterjee S, Coran A, et al. Preliminary report on the International Conference for the Development of Standards for the Treatment of Anorectal Malformations. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40(10):1521–1526. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.08.002. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

17. Stephens FD, Smith ED. Classification, identification, and assessment of surgical treatment of anorectal anomalies. Pediat Surg Int. 1986;1(4):200–205.

18. Pena A, Hong A. Advances in the management of anorectal malformations. Am J Surg. 2000;180(5):370–376. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(00)00491-8. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

19. Rosen NG, Hong AR, Soffer SZ, Rodriguez G, Pena A. Rectovaginal fistula: a common diagnostic error with significant consequences in girls with anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37(7):961–965. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.33816. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

20. Belman AB, King LR. Urinary tract abnormalities associated with imperforate anus. J Urol. 1972;108(5):823–824. [PubMed]

21. Puchner PJ, Santulli TV, Lattimer JK. Urologic problems associated with imperforate anus. Urology. 1975;6(2):205–208. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(75)90712-8. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

22. Senel E, Akbiyik F, Atayurt H, Tiryaki HT. Urological problems or fecal continence during long-term follow-up of patients with anorectal malformation. Pediatr Surg Int. 2010;26(7):683–689. doi: 10.1007/s00383-010-2626-1. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

23. Levitt MA, Patel M, Rodriguez G, Gaylin DS, Pena A. The tethered spinal cord in patients with anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32(3):462–468. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(97)90607-2. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

24. Hong AR, Acuna MF, Pena A, Chaves L, Rodriguez G. Urologic injuries associated with repair of anorectal malformations in male patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37(3):339–344. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.30810. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

25. Warne SA, Godley ML, Wilcox DT. Surgical reconstruction of cloacal malformation can alter bladder function: a comparative study with anorectal anomalies. J Urol. 2004;172(6 Pt 1):2377–2381. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000145201.94571.67. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

II.:-

I refer to the latest published medical contribution of colleagues Fabbro MA, Chiarenza F, D'Agostino S, Romanato B, Scarpa M, Fasoli L, Iannucci I, Pinna V, Musi L , .; Maternal-Pediatric Department. Pediatric Surgery Operative Unit, San Bortolo Hospital, Vicenza, Italy. :-

Pediatr Med Chir. 2011 Jul-Aug;33(4):182-92.

Anorectal malformations (ARM): quality of life assessed in the functional, urologic and neurologic short and long term follow-up.

Fabbro MA, Chiarenza F, D'Agostino S, Romanato B, Scarpa M, Fasoli L, Iannucci I, Pinna V, Musi L.; Maternal-Pediatric Department. Pediatric Surgery Operative Unit, San Bortolo Hospital, Vicenza, Italy.

Source

Maternal-Pediatric Department. Pediatric Surgery Operative Unit, San Bortolo Hospital, Vicenza, Italy. [email protected]

Abstract

Imperforate anus represents a wide spectrum of anorectal malformations associated with urologic, neurologic and orthopedic malformations. The outcome from the various corrective measures has improved due to new surgical techniques as well as to a better understanding of the pathology. Other factors which influence the overall outcome include the degree of patient acceptance, family support as well as the ability of the health care structure to support the patient's needs on a clinical, functional and psychologic level.

AIM OF THE STUDY:

Assess (with the new techniques available) the quality of life in the adult patient with ARM and compare it to that experienced by a younger patient; also we wish to determine the correlation between the observed abnormalities with the functional, neurologic and urologic outcome.

MATERIALS & METHODS:

Sixty-six patients were subjected to PSARP (36 M; 30 F). Six presented with cloaca and 60 with ARM (23 high and 37 low). All patients underwent the same workup to include L/S MRI diagnostics, evaluation for incontinence (urinary and bowel), a urology screening, and if required, a subsequent urodynamic study with rehabilitation and/or bowel management. All answered questionnaires (AIMAR: Italian parent's association of ARM) in order to assess their satisfaction with the current health condition, with the information received and with the treatment and follow-up sessions. The patients were classified into one of two groups. Group A, totaled 33 patients (4 cloacae) with an age range between 2 and 12 years who were operated after 1995. The second, group B, was made up of 33 patients who had been surgically treated before 1995 (age range 15-41 years), had followed the study protocol and had also a neuropsychiatry consult.

RESULTS:

Overall fecal continence was 69% and of this number 37% were clean without constipation. Twe2nty-one patients (32%) suffered from some form of constipation. Constipation was the most common functional disorder observed in patients who have undergone PSARP. The highest incidence of constipation was found in the ARM (low type), a favorable prognostic group with 43% constipation. Patient with "high" defects and a cloaca had a lower incidence of constipation (18%). Of the 59 patients evaluated, 85% were urinary continent and 15% were incontinent. All of the incontinent patients were in the unfavorable prognostic group of malformations. Urodynamic studies showed 7 neurogenic bladders (NB) and 2 patients with a neurovescical dysfunction (NVD). Of the 50 "dry" patients. 20 had voiding disturbances due to a voiding dysfunction, in the absence of neurologic abnormalities, and presented occasional daytime or nighttime wetting. There was no correlation between the level of the anatomic defect and the urodynamic patterns in the group. Abnormal MRI findings were observed in thirty out of fifty-two patients evaluated. The MRI findings were classified as follows. Severe abnormalities: 7 patients (13%) presented with a combination of skeletal (sacral/lumbar) and spinal cord anomalies. Only spinal cord abnormalities: 12 patients (21%). Only skeletal abnormalities: 11 (19%) patients. Patients were divided into high, low and cloacal malformations. A high degree of statistical correlation was noted between the patients belonging to the cloacae and high defect groups and the abnormal MRI findings. No significant correlation was found between the low defect group and dysrafism, abnormal MRI results and the severity of the malformation. The incidence of Tethered Cord (TC) in our limited number of patients was limited in our study (9% in the high and 7% in the low defect group) when compared to the current literature. Furthermore there was no statistically conclusive evidence that TC by itself affects the urinary or fecal control in our patients. Our recommendation is nevertheless to obtain an MRI study in all patients with ARM.

CONCLUSION:

All patients 17 and older reported a "good quality of life". Four are married, two with children. Aclose working relationship with the medical personnel is not only necessary but is also well received by the family particularly when younger patients are involved. The adult patient easily adapts even when information is initially scarce. He quickly reaches autonomy with personalized solutions but prefers a longer follow-up time during which, specialized medical facilities will play an important role in the treatment of ARM. Our findings illustrate the importance of both global disease-specific functioning and perceived psychosocial competencies for enhancing the QL of these patients.

III.:-

I refer to the latest published medical contribution of colleague Risto J. Rintala, Professor of Paediatric Surgery, Hospital for Children and Adolescents, FIN-00029 HUS, Finland in Finland and I also add sections of this paper and give the source of this scientific publication for information: -

Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition:

April 2009 - Volume 48 - Issue - p S79-S82

doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181a15b5e

IV.

Dr. Nabil DEEB about The Universal Declaration of Human Rights ;

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 25 stated quite specifically the right to medical care and health care coverage.

Reiterating the right to health in the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (Article 12), recognized by Europe.

The most important international agreement to protect the right to health is the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (UN - ICESCR), is bound by Germany since 1973.

According to the present Covenant is defined as the right to health as a right of every person for him or her to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health (United Nations - Social and Cultural Rights, Article 12, paragraph 1). This requires the state to create the preconditions, "to make sure in case of illness the medical service and medical care" for one person (the UN - ICESCR, Article 12, paragraph 2 d).

For the purposes of the United Nations - Social Pact opens up the right to health care a right of access to existing infrastructure of public health care. The right to health should be ensured without discrimination, the benefits of health care must be affordable for those affected.

The only legal option, have equal access to sufficient, but not enough. Rather, the access is actually (de facto) are guaranteed. This is not the case if the parties decide not to exercise this fundamental right in most cases because of structural barriers.

Human rights are inalienable rights. They are basically independent status and are therefore fully applicable to women, men and children. The person's health is of primary importance for a life in dignity.

In 2000, 189 countries in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) a clear statement on the global health objectives met and called for a turnaround in global health.

UN human rights treaties: -

ICESCR (social rights):

Article 12:

(1) The Parties recognize the right of everyone to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.

(2) of the States Parties to be undertaken steps towards the full realization of this right shall include those necessary measures

(A) to reduce the number of stillbirths and infant mortality and for the healthy development of the child;

(B) The improvement of all aspects of environmental and industrial hygiene;

(C) The prevention, treatment and control of epidemic, endemic, occupational and other diseases;

(D) The creation of conditions which would assure to all in the event of sickness medical service and medical attention.

As long as people and their governments do not deal in their hearts and their minds together as equals, the international documents such as the so-called '"Universal Declaration of Human Rights'" change in our science society is not much .

http://www.springermedizin.at/artikel/18287-neue-therapie-bei-blutkrebs-in-aussicht

Dr. Nabil DEEB

Arzt – Physician – Doctor

PMI-Aerzteverein e.V.

Palaetinamedico International Aerzteverein – ( P M I ) e.V.

Palestine Medico International Doctors Association ( P.M.I.) registered association .

Department of Medical Research

Département de la recherche médicale

P.O. Box 20 10 53

53140 Bonn – Bad Godesberg / GERMANY

P,S.:

When requesting literatures,

please contact to my address shown

above in GERMANY 53

140 Bonn.

Or

e.mail: [email protected]

http://www.springermedizin.at/artikel/18287-neue-therapie-bei-blutkrebs-in-aussicht

see more puplications from Dr. Nabil DEEB , SEARCH IN Google english an translate these from German into English or Arabic or French languages or in any language

SEARCH IN Google english about

nabildeeb,pmi

nabildeeb,pid

nabildeeb,heart

nabildeeb,cancer

nabildeeb,pmi

nabildeeb.syndrom

nabildeeb, mamma cancer

nabildeeb,depression

nabildeeb,diabetes mellitus

nabildeeb, antioxidants

8/6/2012

" All Rights Reserved To www.paliraq.com "